Many software development teams at one point or another look for that perfect branching strategy, one that would make release management straightforward, while keeping their source repository manageable. More often than not many end up trying heavily promoted Gitflow workflow, without realizing that Gitflow doesn't work for products with more than one actively supported release.

Gitflow Workflow

On the surface Gitflow does sound reasonable. Have a look at Attlasian's Gitflow Workflow tutorial on Bitbucket:

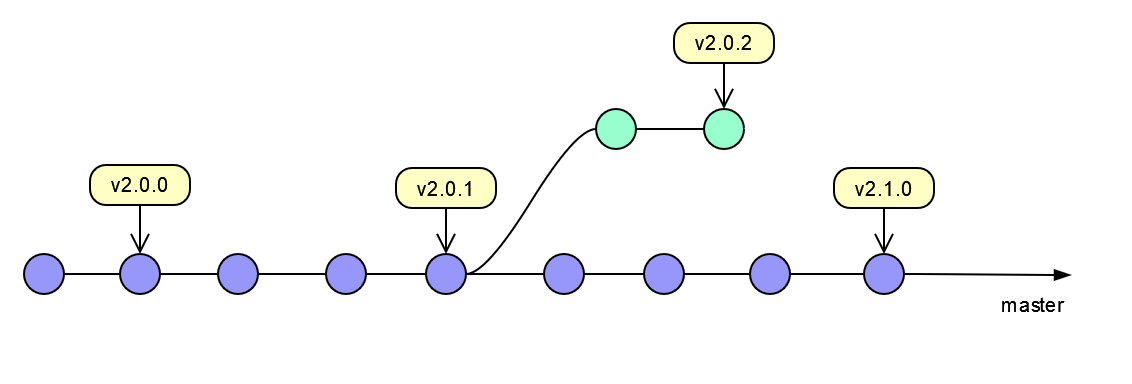

Ignore green feature branches on the bottom of the diagram for now because they come and go throughout the development cycle and have no bearing on release management. It is also not clear why Atlassian would not use semantic versioning for this tutorial and instead used versions v0.1, v0.2 and v1.0. In order to make things easier to compare, here is the same diagram, but without feature branches and with semantic versions.

Yellow boxes on the diagram represent tags, green commits represent release branches, which are created for a specific product release. These branches receive only changes intended for the immediate upcoming release. While a release is being prepared, new development continues on the dev branch without affecting the release. After the release is published, the release branch is merged into master and also into dev, so the former contains only released code and the latter receives all release work. The release is tagged as v2.0.0 only in master.

The process repeats towards the next release, which is v2.1.0 on the diagram. If a bug is found before v2.1.0 is released, a hotfix branch is created off master and is later merged back into master and tagged as a hotfix release v2.0.1. Hotfix changes are also merged into dev for the next release v2.1.0.

Now consider this workflow for a non-website type of a product, where a bug may be reported against one of the past, but still supported product versions. Specifically, consider that after v2.1.0 has been released, a bug is reported for v2.0.1. The user is not yet prepared to take the latest and greatest v2.1.0 and would like just that one bug addressed in a hotfix that would have been v2.0.2, but has no place to go to because v2.1.0 now is in the way.

Gitflow doesn't account for this scenario and people get quite inventive trying to solve this problem and usually end up creating a new branch off v2.0.1 to release v2.0.2 off that branch. This messy process continues and after a while the repository becomes a mess of ad hoc branches and spotty tagging, and the clean diagram above becomes nothing but a distant memory.

Keeping it Simple

Let's refactor the diagram above to make it easier to see how multiple active releases can be maintained.

Notice that master in the original diagram seems to serve very little purpose. The original post promoting Gitflow describes this use of master as a way to make a build off master whenever it receives a new commit, which is possible because master is considered always as production-ready and any commit to master is expected to produce a robust build because all testing was done on the release branch.

While this is a nice sentiment, building from the same source tag does not necessarily mean that the exact same release package will be produced, so this practice of using Git as a build management substitute should be avoided in favor of better ways to manage builds and build artifacts.

Without the master branch (just for discussion purposes), tags and release branches that serve the same original purpose would look like this.

Now it is easy to see that in order to release v2.0.2, all we need to do is to continue the release branch. However, we cannot quite keep repeating the hotfix commit pattern because the merge into master cannot be done after a release branch for v2.1.0 is created, simply because the merge would have nowhere to go. This is where dedicated release branches come in.

Dedicated Release Branches

Let's remove those merge commits for v2.0.0 and v2.0.1 tags, which brings us to a workable branching strategy shown below. This strategy maintains each release branch for as long as necessary to support that version of the product.

In order to support parallel development, a release branch is created when all features for the immediate upcoming release have been decided upon, so development for v2.1.0 can continue on master while v2.0.0 is being finalized on the release branch 2-0-x.

This approach keeps release branches in a well-structured repeatable branch topology and presents a very clean view on what fixes each branch contains. However, it is not without a flaw.

Notice that the release branch never merges into master, which means that changes intended for both, v2.0.0 and v2.1.0, must be cherry-picked between 2-0-x and master. While cherry-picking can be easily done, even for multiple commits, the bigger problem here is that fix A in the diagram above would appear in two dot-zero releases - v2.0.0 and v2.1.0. This requires a process set up, manual or automated, that removes such fixes from the release notes of the newer release, which is an extra release step to maintain, and may get quite messy.

Another negative side effect of this branching strategy is that QA has to verify fix A in the release branch and in master, which means it has to be planned for releases v2.0.0 and v2.1.0 in the issue tracking system, so QA knows where to test this change, but it will be eventually removed from v2.1.0 release notes, which also messes up issue tracking and creates confusion about where the change was really released.

Dot-zero Releases

Dot-zero releases are those with the last component of their version being zero, such as v2.0.0, v2.1.0 and v3.0.0. Dot-zero releases are perceived sequential and the same fix should not appear in release notes of more than one dot-zero release.

This post does not cover more complex multi-level branching strategies that would allow v2.2.0 being worked on after v3.0.0 has been released, which may not necessarily be considered sequential despite the last version component being zero in both of them.

Any product release following a dot-zero release lives its own life and will receive its own fixes that may appear in other product releases as well. In other words, it is expected that v2.0.1 and v2.1.3 could contain the same fix in their release notes for users who could not upgrade to v3.0.0, which may also list the same or a better fix for the same issue.

Development can continue on master until changes intended for the immediate upcoming dot-zero release and for a future dot-zero release need to diverge. When this happens, changes intended for future releases need either to wait for the immediate upcoming release to be finalized or to go on a separate branch. This brings us to two different branching strategies - one is good for smaller teams and projects and one is for more diverse ones.

Updated on 2023-02-05

The term perceived continuity used throughout this post is somewhat ambiguous in that a user running a release following a dot-zero release may still upgrade to the next release, which they will consider as a continous use of released versions.

What this term was originally intended to convey is that the version order and the chronological order of dot-zero releases is always the same and a higher dot-zero release version always follows a lower dot-zero release on the calendar. This means that a resolved issue, such as an implemented feature or a fixed bug, may only appear in at most one of the dot-zero releases because they are sequential and the same issue cannot be released twice.

Releases following dot-zero releases may be released with lower version number and a later date, such as a bug fix in v1.0.1 released after v3.0.0 is released, which in turn requires an additional v3.0.1 release to be made. This post was edited on the date above to provide more context for such releases and how this may affect branching.

Delayed Release Branches

Teams that tend to focus on the upcoming release and do not have much work being done towards the next release following the immediate one would postpone creating a release branch until a dot-zero release is made off master. Any development work that is not going to be released in v2.0.0 can live in feature branches, shown as gray commits below, or simply postponed in patches, or stashes, while the upcoming dot-zero release is being finalized on master.

Change A in this model is committed only on master, which keeps commit A only in release notes for v2.0.0. Changes for releases following a dot-zero release, like change B above, still need to be cherry-picked between branches.

Another, less obvious, but important benefit of this approach is that merges from pending feature branches will be done by a developer who is working on each feature and any merge conflicts will be resolved by a person who is familiar with the incoming changes and can resolve potential conflicts with more understanding of what the final code should look like.

All changes that were introduced in 2.1.0 since 2.0.0, including those in gray commits in feature branches, can be listed with the Git command git log 2.0.0..2.1.0. The equivalent Mercurial command is hg log -r "2.1.0 % 2.0.0".

Release Branches for Parallel Development

The second approach is more suitable for larger teams that cannot keep changes for future releases in feature branches because their changes need to be tested together with other pending changes.

Considering that there is always only one upcoming dot-zero release, the tagged release commit, such as v2.0.0 on the diagram below, can be merged back into master without conflicting with any future release, while the release branch continues, so it can support any additional patches for the v2.0.x product line.

A release branch in this case is created before the dot-zero release, so teams working on features for the future v2.1.0 release, can commit their changes to master, while the dot-zero release team commits their changes to the 2-0-x branch.

Changes intended for v2.0.0 are committed only into the release branch because it will merge back into master after v2.0.0 is released, usually within 2-4 weeks. Change A in this case is committed only to 2-0-x, which also keeps it only in release notes for v2.0.0. However, change B for v2.0.1 is cherry-picked between branches, just like in other cases for releases after any dot-zero release.

From the issue tracking perspective, change A should be verified by QA only on branch 2-0-x and should considered as verified when v2.0.0 is merged back into master simply because released and closed issues cannot be reopened. Any regression resulting from this merge should be tracked with new issues. Change B, on the other hand, should be tracked for releases v2.0.1 and v2.1.0 in the issue tracking system and should be tested in each of the branches before its corresponding issue can be closed as verified.

The downside of this approach, in contrast with the previous simpler branching model, is that one person will have to merge v2.0.0 into master, which means any potential conflicts may need to be resolved by somebody other but the original author. However, given that a dot-zero release is typically being worked on during 2-4 weeks, this merge shouldn't result in too many conflicts.

Similarly to the simpler branching model, git log 2.0.0..2.1.0 and hg log -r "2.1.0 % 2.0.0" will list all changes in 2.1.0 introduced since 2.0.0 for Git and Mercurial, respectively.

Subsequent Release Branch Merges

One desire many will have will be to continue merging the release branch into master after the initial dot-zero release. In the two diagrams above, it means that revision B may be merged into master before branch 2-1-x is created, instead of cherry-picking it onto master. As tempting as it sounds sometimes, such merge may have unexpected side effects.

It's important to highlight that while a dot-zero release will typically be prepared within 2-4 weeks from the moment a release branch was created, the time between a dot-zero release and any other release on that branch may be weeks, months and even years, so in most cases it won't even be possible to merge because there will be other dot-zero releases in the way, like the v2.1.0 release in the diagrams above.

However, even before a branch for the next dot-zero release is created, a possible merge from v2.0.1 shown on the diagram below may introduce inconsistent branching topologies, more complex issue tracking between different target releases and may potentially undo some of the work in master.

The merge shown above will bring into master not only the desired fix B, but also a tactical fix X that was meant only for that specific release and for the next dot-zero release it was implemented more thoroughly as commit X'. This may undo the latter, depending on the nature of the changes. In contrast, changes in a dot-zero release are usually more focused on the upcoming release and are less likely to undo existing work.

Such merge will also make branching for releases following dot-zero releases more complex in that if such release occurs before the next dot-zero release, it can be merged into master and otherwise relevant changes need to be cherry-picked into the releases following the next dot-zero release. In the example above, if v2.0.1 is released after v2.1.0, fix B would need to be cherry-picked into v2.1.1 and v3.0.0, assuming the latter being the next dot-zero release. All development merge instructions and scripts would have to be maintained with the assumption that either of these scenarios may occur.

Another consideration for release branches following dot-zero releases is that their version continuity may not match chronological continuity because these releases can be made at any time between dot-zero releases. This will affect the target version for each issue in the bug tracking system, such as Fix Version in Jira, in that issues must not be mentioned more than once in any of the releases within a continuous sequence, such as dot-zero releases, but may have multiple target versions for releases following the dot-zero ones.

For example, change A may appear in v2.0.0, but not in v2.1.0. Change B, on the other hand, should appear in v2.0.1, 2.1.1 and 3.0.0 if the former was released chronologically after v2.1.0, and only in v2.0.1, if it was released chronologically before v2.1.0. In the latter case the entire v2.0.1 release will be listed in v2.1.0 release notes as en earlier release, along with the change B in it, not just change B among other v2.1.0 changes, as would happen otherwise.

Distinguishing these cases gets quite complicated pretty fast, so people may get creative in tracking issues, such as deciding to clone issues for multiple releases if one of target releases must be made imediately and others could wait their turn when QA become available.

In general, chronologically earlier release may have a single target version, like v2.0.1 above, and otherwise all affected versions should be listed as target releases. In practical terms, this may need to be decided on a case-by-case basis and having both approaches in use can make it more complex to figure out the best approach in each case.

Next Release Focused Branching

Update 2023-02-05

In the recent short while I needed to do some work for Open Source projects where there was no future parallel development, either because these projects were at the end of their life cycle or because all changes were intended only for the upcoming patch release, and the approach described in Delayed Release Branches section produced branching topology with either no commits on master or all of those commits were cherry-picked from the release branches.

This prompted me to revisit my branching approaches for some of these projects and use a simplified form shown on the diagram below.

If there is no parallel development while v2.0.0 and v2.0.1 are being worked on, these releases can be just committed on master and tagged as such, because otherwise master would have no commits of its own, so this topology merely collapses release branches into master.

If a bug fix is required for any of those releases after a newer release was made, like v2.1.0 above, a branch can be made when the work is being done.

Interestingly enough, for one of the releases where all of the release changes were cherry-picked on otherwise empty master, I ended up adding that entire previous release into the release notes for the future release on master, as if a branch was merged, because this is what I ended up with based on the chronological release order, despite how topology looked like.

Final Thoughts

Branches contain sequences of commits representing implemented requirement-level work items, such as user stories, architectural requirements and bugs, between two release tags - the previous release on the left and a potentially non-existing one on the right, with increasing code maturity for each change towards the final release commit, which eventually be tagged with a release version tag.

Branching may get fairly complex, as is evident from this post, and piling up additional purposes for source repositories will only make them more convoluted and harder to maintain. Good examples of such uses are team-specific branches, branches maintained for the purposes of selecting subsets of commits to reach the build system, branches for dependencies, and so on.

Gitflow has some goodness in it, such as having release branches to allow parallel work beween the upcoming release and the next one, and provides a well-described branching pattern for the eitire team, but it also promotes the use of the main branch in the way that cannot accommodate fixes for past releases, as well as it implicitly suggests branching based on how the repository is used, as opposed to what it contains, by using terms like development branch and intergration branch, which some people take further on this path with team branches and other uses beyond just maintaining the source.

Peronally, I think a well-defined and consistent source repository topology is more manageable, even if it leaves some things less optimal than they could be otherwise. Avoiding merging release branches after dot-zero releases is a good example because it requires different handling, depending on whether such releases precede or follow the next release, so I tend to think that cherry-picking changes into the main branch is easier to manage. Gitflow does provide consistent topology, but only for website-type of applications, where there are no past releases to support, and will be difficult to manage for most projects with long-term support releases.

Diagrams in this post are created with app.diagrams.net.

Maybe I'm missing some bit, but assuming that support/3.2.1 is a name of a single branch and not branch support and branch 3.2.1, isn't it the same as maintaining release branches after dot-zero releases, as described in this post?

The issue with keeping unwanted "tactical" fixes out of master can be solved with the "support" or "maintenance" branching pattern.

At some point the team decides that a version of the code will be supported or maintained separately, and those releases start going into a support/3.2.1 naming pattern.

These branches only receive tactical commits and cherry-picked commits from newer development as required to meet maintenance specs only, and are NEVER merged back into an other branch.

This is heavily used by libraries that must back port security fixes to some far flung histories, possibly years old.

So there is still pain (unavoidable if there is a maintenance split) but at least the pain is isolated and does not pollute the main development branches.

Thanks, Joe. I am planning another post for squash commits, where I want to cover feature branches and various scenarios working with them, so more will be there (maybe in 2-3 weeks, or so).

As a short comment here, I find squash commits useful only when original commit descriptions are meaningless, like "addressed code review comments", so a squash can change them into a meaningful self-contained commit that can be associated with an issue, cherry-picked for a bug fix, make it easier to track past work, etc.

As for branches, there's no single answer here, really - a feature branch with meaningful commits merged into its base branch can make it easier to track somebody's work as a thread of changes, as opposed to commits from different people intermixed in on a single branch, for example. Smaller work with a couple of commits, doesn't benefit from it and rebasing them keeps branches better organized.

I will give it some thought. Maybe there's another post in there.

i wish i had this article six years ago. Instead, knowing very little about branch management at the time i stumbled my team into a bastardization of a couple patterns here.

Wondering if you have resources/opinions about what types of merges to use and when? i've always tried to FF whenever possible, but it's not always possible, and often keeps junk/fixup commits in the history that rightfully should have been squashed. i'd like a clean master branch, but keep the tangle of a merge commit minimized.

Just looking for suggestions. Thanks for this article.

I used draw.io for diagrams, which now is app.diagrams.net.

Very well written! Makes it very easy to understand. Also, what did you use to make your Gitflow graphics?

Great Article! Very insightful and obviously a lot of actual hands-on real world experience has flown into this :-)